Decades ago, when JC polyomavirus (JCPyV) was first isolated, scientists could hardly have imagined that the small non-enveloped DNA virus could be a candidate for the etiological agent of human malignancies. Today, however, JCPyV is already on the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Group 2B (“possibly carcinogenic to humans”) list, primarily because of the presence of the genetic information for strong oncoproteins, such as the large T antigen. As knowledge about viral oncology has been progressing, a number of questions have arisen in the minds of scientists concerning JCPyV: how does it enter and infect humans? why does it persist for so long in the body? and, most importantly, does it have the potential to cause cancer? This article reviews the biology of JCPyV, including infection and persistence in the body and recent advances in tumor development.

What Is JCPyV?

Polyomaviruses are small, non-enveloped viruses with icosahedral symmetry and circular double-stranded DNA genomes. They were originally discovered in mice, where infection could trigger tumors in multiple organs—thus the name poly-oma. In 1971, researchers identified the first human polyomavirus while studying the brain tissue of a patient named John Cunningham, who suffered from progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML)—a severe demyelinating disease of the central nervous system. The virus was named JC polyomavirus in his honor.

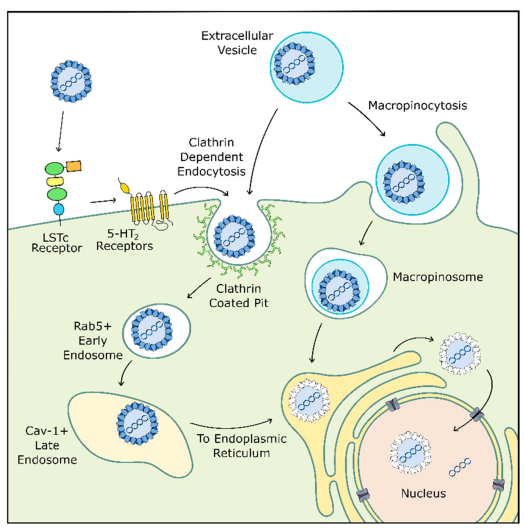

Figure 1. JCPyV cellular entry may occur through multiple pathways.(Source: Atkinson AL, et al.; 2020)

Around the same time, another human polyomavirus, BKPyV, was isolated from a kidney-transplant patient. Since then, scientists have identified more than ten human polyomaviruses, including the now well-known Merkel cell polyomavirus, which is definitively linked to Merkel cell carcinoma.

Although JCPyV infection is extremely common—70–80% of adults carry antibodies—its disease manifestations are rare. Most primary infections occur during childhood and are clinically silent. After this initial encounter, the virus goes into hiding.

Where Does JCPyV Hide?

Once inside the body, JCPyV establishes latent, persistent infections in multiple tissues, including:

- Tonsils

- Bone marrow

- Lymph nodes

- Kidney and urinary tract epithelium

- Gastrointestinal tract epithelium

The virus is generally latent and does not express significant amounts of protein. However, in the case of immune suppression -such as AIDS, organ transplantation, chemotherapy or treatment with immunomodulatory drugs- JCPyV can reactivate. Reactivation in glial cells (predominantly oligodendrocytes) leads to PML, an often lethal neurological condition.

Interestingly, JCPyV strains differ. The non-coding control region (NCCR) is a regulatory DNA segment that determines replication efficiency and pathogenicity.

- Prototype strains, common in healthy individuals, replicate poorly.

- Rearranged mutant strains, typically isolated from PML patients, replicate aggressively.

These strain differences may hold clues to the virus’s oncogenic potential.

How JCPyV Might Promote Cancer

JCPyV’s ability to interfere with cell cycle regulation and genomic stability largely stems from three early proteins:

Large T Antigen (LTag) – the heavyweight oncogene

LTag is essential for viral DNA replication and is the principal driver of cell transformation. Its functions include:

- Binding and inactivating p53, blocking apoptosis and DNA repair

- Binding proteins of the retinoblastoma (Rb) family, forcing cells prematurely into S-phase

- Interacting with β-catenin, stabilizing it and boosting transcription of oncogenes like c-myc and cyclin D1

- Binding IRS-1, interfering with DNA homologous recombination repair

- Activating survival pathways and blocking apoptosis

In essence, LTag dismantles the cell’s genomic “security systems” while pushing it to proliferate—conditions ripe for cancer development.

Small T Antigen (sTag) – the co-conspirator

sTag shares its N-terminal sequence with LTag but has a unique C-terminal PP2A-binding domain. PP2A is a major cellular phosphatase regulating growth-signaling pathways. By inhibiting PP2A, sTag helps create a pro-oncogenic environment and can enhance the transformative power of LTag.

Agnoprotein (Agno) – the mysterious regulator

Originally named for its “unknown” function, Agno is now recognized as a multifunctional modulator. It participates in:

- Viral transcription and replication

- Host cell cycle control

- Direct interactions with p53

- Suppression of DNA repair via binding to Ku70

Through these interactions, Agno may contribute to genomic instability, a hallmark of many cancers.

Evidence From Animal Models

Animal studies have long provided strong support for JCPyV’s oncogenic capacity:

- Injection of JCPyV into newborn hamsters produces medulloblastomas, astrocytomas, and glioblastomas.

- Similar results occur in squirrel monkeys.

- Importantly, tumors in these animals consistently express LTag, even when no viral replication is detectable.

Moreover, mice engineered to express the JCPyV LTag gene spontaneously develop tumors in various organs, confirming LTag as a functional oncoprotein in vivo.

Is JCPyV Linked to Human Cancer?

Although direct proof remains elusive, numerous studies have detected JCPyV DNA or proteins in human tumors—including:

- Central nervous system tumors

- Medulloblastoma

- Astrocytoma

- Glioblastoma

Multiple studies since 1999 have found high viral copy numbers and LTag expression in medulloblastoma samples, sparking considerable interest in JCPyV’s neurological oncogenicity.

Colorectal Cancer

Findings suggest several possible roles:

- Chronic latent infection may create a pro-inflammatory microenvironment

- Expression of LTag, sTag, and Agno could induce genetic instability

- Viral proteins may act as “cofactors” rather than direct carcinogens

While still debated, JCPyV remains one of the most frequently detected viruses in colorectal tumors worldwide.

Urinary Tract Cancers

Because JCPyV commonly persists in the urinary epithelium, investigators have explored its association with:

- Bladder cancer

- Prostate cancer

High viral load and LTag expression have also been detected in tumor tissues in some studies, but small sample sizes and the absence of validated human cell models remain limitations and results are still considered preliminary.

Future improvements like urine-based liquid biopsy, next-generation sequencing for NCCR mutations, and well-established epithelial cell models could provide some answers.

The Future of JCPyV: What’s the Big Deal?

Improved sequencing, genome editing tools, and viral diagnostic assays in recent years have re-energized the human polyomavirus field. For JCPyV, key outstanding questions include:

- What triggers its shift from latency to active expression of oncogenic proteins?

- Why does it appear in certain tumors but not others?

- Do NCCR rearrangements influence its oncogenic behavior?

- Can JCPyV act as a co-factor that supports tumor growth initiated by other carcinogens?

Understanding these mechanisms could ultimately lead to better screening tools, diagnostic markers, and therapeutic strategies—especially for cancers arising in tissues where JCPyV naturally resides.

Conclusion

JCPyV is an almost panmictic virus with a Janus-face identity as a quiescent bystander in most individuals but as a latent threat under certain circumstances. Although the involvement of JCPyV in human cancer has not been conclusively shown, the available data including many years of molecular, cellular and animal studies strongly suggest that JCPyV oncoproteins, particularly LTag, can perturb multiple regulatory pathways and contribute to oncogenic transformation. The ongoing elucidation of JCPyV biology as new technologies become available is likely to add to our understanding not only of viral oncogenesis but also of genomic instability and tumor evolution more generally. The JCPyV story is not yet fully told—but it is getting more interesting all the time.

Reference

1. Atkinson AL, Atwood WJ. Fifty Years of JC Polyomavirus: A Brief Overview and Remaining Questions. Viruses. 2020, 12(9):969.

| Cat. No. | Product Name | Application | |

| DEIASL160 | CDJCVᵀᴹ Anti-polyomavirus JC (JCV) IgG ELISA Kit | Qualitative / Semi-quantitative | Inquiry |